A young Monash University chemist and her colleagues have successfully strengthened insulin’s chemical structure without affecting its activity. Their new insulin won’t require refrigeration.

They have just filed a series of patents with the support of their long term commercial partner ASX-listed Circadian Technologies who are now negotiating with pharma companies to start the long process of getting the invention out of the laboratory and into the homes of people with diabetes.

At the same time they’re using their new knowledge to develop a form of insulin that could be delivered by pill.

“Over two hundred million people need insulin to manage diabetes, but we still don’t how it works at a molecular level,” says Bianca van Lierop.

Her work will be presented for the first time in public this week at Fresh Science, a communication boot camp for early career scientists held at the Melbourne Museum. Bianca is one of 16 winners from across Australia.

The poor stability of existing forms of insulin complicates the management of diabetes, a condition which already affects 1.7 million Australians.

“Like milk, insulin formulations need to be kept cold,” Bianca says.

“At temperatures above 4 ºC, insulin starts to degrade and eventually becomes inactive. So supplying insulin in areas where fridges are scarce or difficult to maintain presents a real challenge.”

The instability of insulin is closely related to its chemical structure, Bianca says.

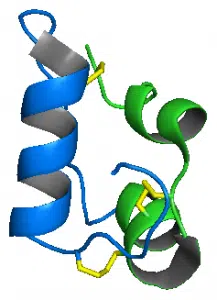

“Insulin is constructed from two different protein chains which are joined together by unstable disulfide bonds. Using a series of chemical reactions, we have been able to replace the unstable bonds with stronger, carbon-based bridges. This replacement does not change the natural activity of insulin, but it does appear to significantly enhance its stability.”

These so-called ‘dicarba insulins’ are stable at room temperature. And, Bianca says, storage at higher temperatures for several years had not resulted in degradation or loss of activity.

The new insulins may also provide much-needed insight into how the molecule works. “Insulin acts like a key in a lock at its receptor. When insulin binds to the receptor the lock opens and allows sugar to be taken up into cells from the blood. But insulin is known to change shape inside the ‘lock’ (the receptor), and its final shape is currently unknown.”

“If we had that information, we might be able to design smaller, less complex, non-protein mimics of insulin.” Such molecules could one day become the basis of treatments taken in pill form, eliminating the need for injections.

Bianca van Lierop and her fellow Fresh Scientists are presenting their research to the public for the first time thanks to Fresh Science, a national program sponsored by the Australian Government. Her challenges include presenting her discoveries in verse at a Melbourne pub.

For further information, contact Bianca van Lierop at Bianca.vanLierop@monash.edu

Additional Images

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.