Australian researchers have revealed a new pattern of ocean circulation which will change our understanding of marine events.

Research at the University of Melbourne and the Bureau of Meteorology has overturned conventional ideas of ocean circulation.

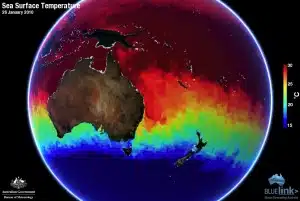

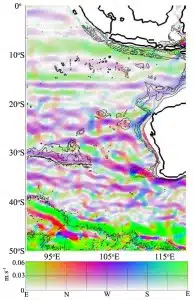

Rather than moving simply in large clockwise (northern hemisphere) and anti-clockwise (southern hemisphere) gyres, the open waters of the southeast Indian Ocean are flowing east-west in bands, Prasanth Divakaran, a PhD candidate in the University’s School of Earth Sciences, and his colleagues have shown.

The findings have important implications for our understanding of all sorts of ocean events from the movements of fish and marine life to the prediction of weather and climate.

“For instance,” he says, “We found that ocean eddies—the marine analogues of atmospheric weather systems like tropical cyclones—form off Australia and begin a three-year journey across the Indian Ocean along what we call ‘ocean arteries’, transporting sea-water and biology with them.”

Prasanth’s work is being released for the first time in public through Fresh Science, a communication boot camp for early career scientists held at the Melbourne Museum. He was one of 16 winners from across Australia.

Prasanth is also presenting his research at the XXV International Union of Geophysics and Geodesy General Assembly in Melbourne this week.

On the basis of initial studies of water movement, Prasanth analysed a model of the circulation of the southeast Indian Ocean using advanced computing and new software for visualising the results. He and his colleagues then checked their findings against satellite observations.

“New international satellites and modern technologies developed in Australia helped to reveal the previously unknown ocean circulation patterns.”

The results are also in keeping with some of the latest research from overseas, he says.

The basin-wide ocean currents the researchers revealed are organised into alternating bands, which connect the north-south currents on the east and west side of the Ocean.

“They look a bit like the patterns seen on the surface of Jupiter.”

Recent work on the lobster life cycle around Western Australia has shown that the probability of growing into an adult depends on which deep artery of ocean circulation the larvae are swept into.

“Nature has known about these ocean arteries for centuries, but we humans have only just discovered them.”

Understanding the impact of the arteries on ocean heat transport and climate is critical, Prasanth says.

- For interviews, contact Prasanth Divakaran on 0421 936 761 or p.divakaran@bom.gov.au

- For Fresh Science, contact AJ Epstein on 0433 339 141 or aj@scienceinpublic.com.au, Sarah Brooker on 0413 332 489 or Niall Byrne on niall@scienceinpublic.com.au

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.