A newborn’s first breath is an emotional moment. It’s also crucial for clearing the liquid that previously filled their lungs, which helps a fetus grow and develop.

“But newborns who don’t effectively clear their lungs as they’re coming into the world can’t get enough oxygen, putting them at risk of complications and admission to the neonatal intensive care unit for breathing support,” says Dr Erin McGillick.

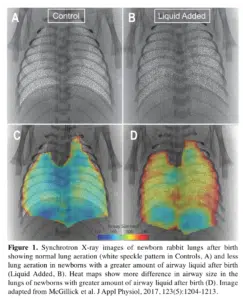

Erin is based at the Hudson Institute of Medical Research and Monash University. She has been using light from both the Australian Synchrotron and the Japanese SPring-8 Synchrotron to study newborn rabbits, to help understand how newborns make the transition to air-breathing.

“My research has shown that when newborns have more liquid in their lungs at birth, it’s harder to get enough air in. Then when they breathe out, that extra liquid may fill the airways, which reduces lung function further,” Erin says.

“This work provides evidence underlying a common newborn respiratory complication.”

The Synchrotron accelerates electrons to close to the speed of light, producing X-rays one million times brighter than the sun. This has allowed Erin to see what’s happening in the lungs of newborn rabbits from the very first breath.

Erin’s future work will involve finding ways to help newborns clear the extra liquid, informing therapies to improve their lung function and ultimate outcomes.

“I hope this work will ensure the best possible start to life for newborn babies,” Erin says.

Erin is spending three months in early 2018 at the Leiden University Medical Centre in the Netherlands, getting her first taste of clinical research to improve the transition to breathing at birth for premature babies.

Erin has conducted experiments at the Australian Synchrotron and the Japanese SPring-8 Synchrotron. Credit: Erin McGillick

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.