A biotechnologist from the South Australian Research and Development Institute has taken using “everything but the pig’s squeal” to new lengths. Through clever recycling of pig waste, Andrew Ward has been able to produce feed for aquaculture, water for irrigation, and methane for energy. His ‘waste food chain’ can be applied to breweries, wineries and any system producing organic waste.

He’s done it by taking traditional approaches from China, India and Vietnam, some new ideas and a lot of streamlining and integration to make a system that will meet Australian needs and standards.

His work has been underwritten by the Environmental Biotechnology Cooperative Research Centre (CRC) and pulls together ideas from Murdoch University, SARDI, The University of Adelaide and the CRC.

“We can turn waste into food, save money, save water, and improve the environment just by being a bit smarter,” Andrew says.

His work will be presented for the first time in public this week at Fresh Science, a communication boot camp for early career scientists held at the Melbourne Museum. Andrew is one of 16 winners from across Australia.

“We are hoping this research will lead to elimination of the environmental concerns and costs associated with waste disposal, and that the wastes themselves can be transformed into new and diversified business opportunities,” Andrew says.

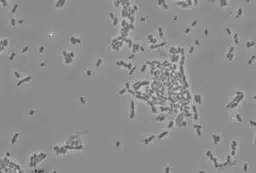

The pig effluent is initially fed into an airtight, two-stage digester. This breaks down the chemical compounds that smell and kills potentially dangerous bacteria, while at the same producing methane bio-gas as well as nutrients which can be used to stimulate the growth of tiny seaweeds or microalgae.

Andrew’s studies showed that the digested piggery effluent is a safe nutrient source for the commercial scale production of algae which can then be used for aquaculture.

“Once we had the algae growing, we knew we could recreate the ocean food chain from algae to zooplankton to fish,” he says.

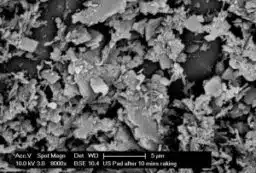

“We use two small native South Australian water fleas, Moina australiensis and Daphnia carinata, which can form the basis of commercial fish meal. By carefully establishing the best conditions for growth and reproduction, the water fleas can be produced more quickly than with existing methods. This makes the system more efficient and the technology financially viable.

What’s more, the zooplankton help to clean up the water in which they grow, by reducing the levels of nutrients and bacteria. They do such a good job, that the water can subsequently be used for irrigation.

Andrew thinks similar bio-treatment systems can be established to handle the liquid and solid waste from other livestock industries. “This integrated production technique is pioneering work in Australia,” he said. “We hope it will present a shift in thinking for business where they begin to regard waste no longer as a cost, but as an income stream.”

Andrew Ward is one of 16 early-career scientists presenting their research to the public for the first time thanks to Fresh Science, a national program sponsored by the Australian Government. His challenges include presenting his discoveries in verse at a Melbourne pub.

- This work was funded by the Environmental Biotechnology Cooperative Research Centre

For further information, contact Andrew Ward at andrew.ward@adelaide.edu.au

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.