A new system for directing radiation to target cells has been developed in Melbourne. The new targeting system has the potential to specifically destroy cancer cells with minimal damage to healthy tissues.

The new targeting concept, for which an international patent is pending, uses a special class of radioactive atoms for which the radiation damage is confined to the molecules immediately adjacent to the radioactive atom.

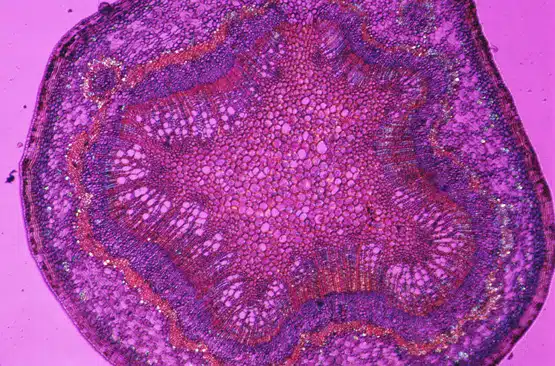

The cell-killing effect is maximised by directing the radiation to the genetic material (DNA) of the target cell, with little effect on neighbouring cells.

“We expect that our targeting system will be particularly useful for small clusters of cancer cells, such as those that spread throughout the body when a cancer becomes more advanced,” says Dr Tom Karagiannis, research officer with the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre where the system was devised.

Conventional cancer therapies such as surgery, radiotherapy and chemotherapy have resulted in a steady decline in cancer mortality rates over the years. Only chemotherapy has the potential to be effective when the cancer has spread throughout the body, but often it is not effective.

Latest figures from the World Health Organization show that about 50 percent of cancer patients still die in developed countries and about 80 percent die in developing countries.

A unique feature of the cancer targeting system is the highly focussed damage caused by the radioactive isotopes used – most of the radiation damage is within a distance of only a few millionths of a millimetre. This means they can kill cancer cells without causing significant damage to normal cells.

The new technology combines knowledge from a wide range of scientific disciplines, including radiation biology, chemistry and immunology, Dr Karagiannis says. The key ingredient is a complex composite drug, made by attaching the radioactive atom to a DNA-binding molecule, which in turn is linked to a cancer-targeting protein such as an antibody.

“Our radiolabelled DNA-binding drug alone provided a very efficient ‘molecular bomb’ for destroying cells,” says Dr Karagiannis. “But it could not discriminate between cancer cells and healthy cells.”

To make a ‘smarter’ drug, researchers took advantage of the fact that many cancer cells express high levels of certain proteins on their cell surface. Antibodies that bind specifically to these surface proteins were used as vehicles to target the lethal damage to cancer cells.

“Our strategy builds on the growing interest in antibodies as cancer therapeutics,” says Associate Professor Roger Martin, Tom’s supervisor who has been working on the project concept for the past three decades.

“There are a currently only a handful of such anticancer-antibodies that have been approved for therapy and many others that are in clinical trials.”

Proof-of-principle studies with the new targeting system have yielded very promising results with cell cultures, but a commercial partner is required for further development.

Tom is one of 13 Fresh Scientists who are presenting their research to the public for the first time thanks to Fresh Science, a national program sponsored by the Federal and Victorian Governments. One of the Fresh Scientists will win a trip to the UK courtesy of the British Council to present his or her work to the Royal Institution.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.