A patented treatment could restore eyesight for millions of sufferers of corneal disease.

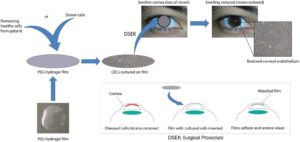

The University of Melbourne–led team of researchers have grown corneal cells on a layer of film that can be implanted in the eye to help the cornea heal itself. They have successfully restored vision in animal trials and are aiming to move to human trials next year.

Over 2000 corneal transplants are conducted in Australia each year. But globally there’s a shortage of donated corneas, and the resulting loss in vision affects about 10 million people worldwide.

“We believe that our new treatment performs better than a donated cornea, and we hope to eventually use the patient’s own cells, reducing the risk of rejection,” says Berkay Ozcelik who developed the film working at the University of Melbourne.

“Further trials are required but we hope to see the treatment trialled in patients next year,” he says.

The cornea is the transparent layer at the front of the eye. To remain healthy and transparent, the cornea must remain thin. A layer of specialised cells (corneal endothelial cells) on its inner surface maintain the cornea’s moistness by ‘pumping’ water out of it.

However, trauma, disease and aging can reduce the numbers of these cells, eventually causing the cornea to become swollen and cloudy, leading to vision deterioration and blindness.

The cells cannot regenerate or repair themselves. The only treatment available requires donor corneas to be transplanted into the patient’s eyes. But there’s a worldwide shortage of donor corneas. The transplant process damages some corneal endothelial cells, and the donor cornea may still be rejected by the patient’s immune system.

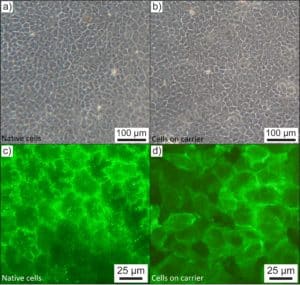

Berkay and his colleagues grew corneal cells on a specially developed synthetic film that could then be implanted into a patient’s eye.

“The hydrogel film we have developed allows us to grow a layer of corneal cells in the laboratory,” says Berkay. “Then, we can implant that film on the inner surface of a patient’s cornea, within the eye, via a very small incision.” Once in place the new cells restore the cornea’s vital water-pumping activity, so that the cornea once more becomes transparent.

Thinner than a human hair (50µm), the hydrogel film is perfectly transparent when implanted, and allows the flow of water between the cornea and the interior of the eye. The film completely biodegrades within two months and causes no adverse immune reactions.

Berkay developed the synthetic film used to culture new corneal cells at the Polymer Science Group (the University of Melbourne), working with the Centre for Eye Research Australia. Berkay is now working in a similar field at CSIRO and is still active with the corneal film project as an Honorary Post-doctoral Fellow at the University.

Berkay was the Victorian winner of Fresh Science, a national program helping early-career researchers find and share their discoveries, supported by Museum Victoria, CSIRO, Deakin University, Monash University, RMIT University, Swinburne University of Technology, the University of Melbourne and New Scientist.

Read about the cornea https://nei.nih.gov/health/cornealdisease

Contacts:

- Berkay Ozcelik (researcher) ozcelik@unimelb.edu.au, 0422 349 434

- Greg Qiao (Project Supervisor) gregghq@unimelb.edu.au, 0439 392 512

- Mark Daniell (ophthalmic surgeon) daniellm@unimelb.edu.au

- Errol Hunt (media) errol@scienceinpublic.com.au, 0423 139 210

- Michael Grigoletto (Centre for Eye Research Australia) grigoletto@unimelb.edu.au, 0417 560 743

- Joy Francisco (The University of Melbourne) francisco@unimelb.edu.au, 03 8344 3147

- Jordan Green (The University of Melbourne) green@unimelb.edu.au

.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.