From tropical savannas in the Territory to old growth rainforest in Tasmania, Australian forests may adapt to changing temperatures over time

Forests are a major carbon sink, responsible for about three quarters of carbon absorption on land, a critical buffer against rising carbon levels in the atmosphere from climate change.

As the temperature rises, ecologists are worried about the effect on trees’ capacity to remove carbon from the air, because photosynthesis – the process by which trees and all plants turn carbon dioxide into sugars for growth – is very sensitive to temperature changes.

But new research from the University of Melbourne has shown that Australian forests may be more resilient than we thought to temperature rises.

PhD Candidate Alison Bennett, who led the work, found that our trees photosynthesise at their maximum rate at the temperatures in which they grow. This means there’s a chance they’ll be able to adjust even in the face of recent, small increases in the average daytime temperature.

“Trees are the best carbon capture technology we have – humans haven’t been able to invent anything better,” says Alison. “They play a really important role in capturing carbon dioxide from the air through photosynthesis, and storing it as biomass in their wood, leaves and roots.”

“Our discovery shows that the carbon uptake capacity of forests hasn’t yet been disrupted by temperature rises, which is reassuring given how critical they are in the carbon cycle.”

Australian forests store about 21.7 billion tonnes of carbon, equivalent to 79.5 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide – that’s 150 times Australia’s annual carbon dioxide emissions – so tree planting and forest preservation are key planks in Australia’s strategy to reduce carbon in the atmosphere.

But the researchers warn that while our forests have proven resilient so far, we still need to mitigate against climate change and keep rising temperatures below 1.5°C.

“Our discovery shows that ecosystems may have some capacity to adjust to the changing climate ,” says Alison Bennett. “While that’s good news, rising temperatures bring other risks, like fire, heatwaves, drought, extreme weather, pests and diseases, which will also affect our forests.”

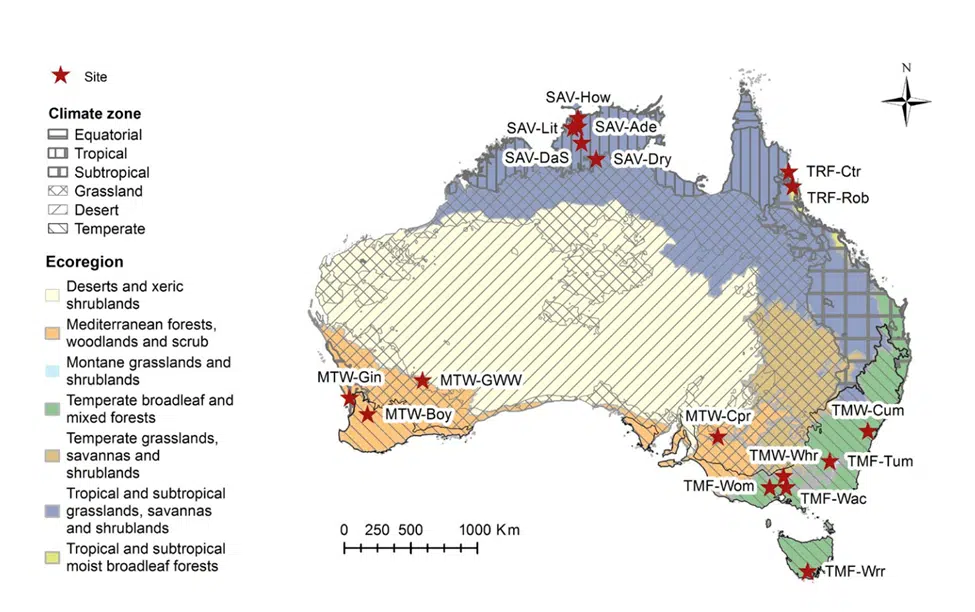

Alison looked at a range of ecosystems across the country: tropical forests in North Queensland; tropical savannas in the Northern Territory; Mediterranean woodlands in South and Western Australia; temperate woodlands in New South Wales and Victoria; and temperate forests across Southeastern Australia.

This range was only possible thanks to the TERN research infrastructure: dubbed “Australia’s land ecosystem observatory”, it gathers technical data about land ecosystems at hundreds of sites across the country.

“TERN research infrastructure is really important for understanding our forests. TERN funds the critical infrastructure used by the OzFlux network to monitor carbon dioxide uptake in these forest ecosystems. Without this infrastructure and the dedicated scientists at OzFlux who have been collecting and collating data for many years my research would not have been possible.”

This work was supported by the use of Terrestrial Ecosystem Research Network (TERN) infrastructure, which is enabled by the Australian Government’s National Collaborative Research Infrastructure Strategy (NCRIS). Alison is also supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship at the University of Melbourne.

For further info:

- Bennett, A. C., et al. 2021. Thermal optima of gross primary productivity are closely aligned with mean air temperatures across Australian wooded ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.15760

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.