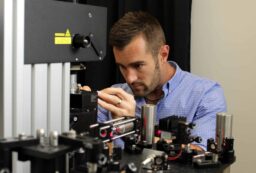

Could Australia rise to the top of the diamond pipe again? Macquarie University researcher Craig O’Neill believes his research could open new diamond fields across Australia.

It turns out that diamonds are not forever after all. And that may be a good thing for Australia’s $100-million a year diamond industry.

By determining how and where diamonds form, disappear,

and re-form, geoscientists from Sydney’s Macquarie University can now indicate the best places to look for them. And in Australia that means a broad arc of country stretching from the Kimberleys to southwest Queensland.

“Australia is facing a diamond drought,” says research team leader Dr. Craig O’Neill, from the National Key Centre for Geochemistry and Metallogeny of Continents (GEMOC). “We hope our work can help the Australian industry find more diamonds and grow to become the biggest in the world again.”

By combining laboratory results on the behaviour of rocks and diamonds under pressure, O’Neill and colleagues have been able to simulate using computers the conditions deep under the Earth’s continents, where diamonds form. Their results suggest that diamonds may be much more widespread than previously thought.

“People used to assume that once formed, diamonds were pretty much indestructible, and stayed fixed in one place at the bottom continents. It took some violent event, such as a volcanic eruption to bring them to the surface,” says Craig. “But we found that down where they actually form, it’s more mushy than solid rock, and the diamonds, far from being indestructible, can really take a beating, sometimes being destroyed entirely.”

“The challenge is actually getting them to the surface,” says O’Neill. “That requires a very violent type of volcanism called kimberlites. These are like geological atomic bombs. Fortunately they’re pretty rare.”

The research suggests a number of places to start digging. “In order to find diamonds at the surface, you need both diamonds deep underground and kimberlite volcanism. That seems to happen mostly where thick and thin pieces of continent are sandwiched together,” says Craig.

In Australia, this occurs in a broad swathe from the Kimberleys in Western Australia, across the Northern Territory to southwest Queensland.

“The most interesting part is what the work tells us about processes deep underground. The Earth has a whole secret life happening down there we know very little about.”

Craig O’Neill is one of 16 Fresh Scientists who are presenting their research to school students and the general public for the first time thanks to Fresh Science, a national program hosted by the Melbourne Museum and sponsored by the Federal and Victorian governments, New Scientist, The Australian and Quantum Communications Victoria. One of the Fresh Scientists will win a trip to the UK courtesy of the British Council to present his or her work to the Royal Institution.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.