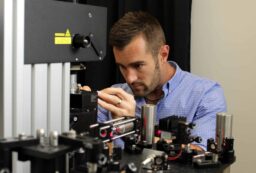

Silk could provide a sophisticated new way of monitoring health, Peter Domachuk, a physicist from the University of Sydney, has found.

The bombyx Morii s ilk moth whose cocoons are used for extracting the fibron (photo: Peter Domachuk)

He and his colleagues have created microchips using silk fibres. In the lab they’ve demonstrated that these microchips can measure oxygen using haemoglobin embedded in the silk.

Their aim is to embed a wide range of proteins so they can run dozens of blood test simultaneously at the point of care instead of waiting for the pathology lab.

“We hope that within the decade our silk chips will be at work in every hospital, GP clinic and home,” says Peter who developed the idea of using natural fibres in medical devices while working with Fiorenzo Omenetto and David Kaplan at Tufts University, Boston USA.

Silk fibres, he says, can be formed into tiny platforms or “bio-chips” that should allow medical testing and measuring of vital signs to be undertaken more rapidly and cheaply than current technology allows. His work will be presented for the first time in public this week at Fresh Science – a national science talent search – at the Melbourne Museum. Peter is one of 16 winners from across Australia.

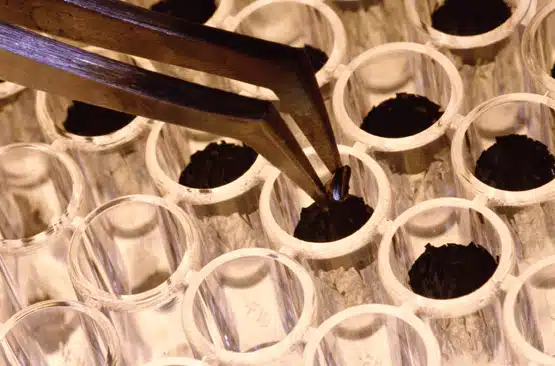

The protein that underpins the strength of silk, fibroin, can be purified to form a clear material that can be used to display tiny drops of thousands of different biochemical compounds in patterns where they are no farther apart than the width of a human hair. These test compounds can then be simultaneously exposed to and react with body fluids such as human blood.

“The particularly interesting thing about silk,” Peter says, “is that the biochemical compounds it holds retain their activity. This biochemical activity

enables extra sensitivity for monitoring and detecting medical conditions. And fibroin is transparent and can be formed into structures to control light which can be then used as a sensitive probe for improved medical testing. What’s more, silk doesn’t trigger the human immune response when it comes into contact with tissue.”

The above combination of factors makes silk a unique candidate for implantable biochips—devices like electronic microchips that can sit in or under the skin a

nd detect chemicals in the blood. This can allow quick and accurate determination of medical conditions without the need for expensive laboratory-based pathology.

“I’m confident that the technology can lower healthcare costs and reduce patient risk,” Peter says.

Peter Domachuk is one of 16 early-career scientists presenting their research to the public for the first time thanks to Fresh Science, a national program sponsored by the Australian Government. His challenges include presenting his discoveries in verse at a Melbourne pub.

For further information, contact Peter Domachuk at peter.domachuk@sydney.edu.au

Additional Photographs

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.

Fresh Science is on hold for 2022. We will be back in 2023.